Article by:

Dr. Mohamad Hussein Mansour,

Lecturer at the American University of Beirut

Lecturer at the Lebanese American University

Rasha Fattouh

Lecturer at the Beirut Arab University

Joe Akiki

American University of Beirut

The year 2020 has been dictated by the ever-growing spread of the pandemic. The exponential proliferation of Covid-19 has caused entire economies to cease operations as the number of cases and subsequent deaths keep rising. As policymakers weigh the health costs of the pandemic to its economic losses, and as they frantically try to decide the extent and intensity of lockdowns, the global economy has endured a devastating shock. With the frequent shutting down of businesses, education centers, and restrictions on travel, confidence levels have plummeted as consumption and investments have reached new lows. As a result, supply chains, world trade, and the touristic sector were heavily disrupted and the financial, commodity, and stock markets experienced extreme volatility. The efforts exerted in controlling the pandemic and containing it have triggered exceptional demand and crash in oil prices. Considering the speed of which the crisis has dominated the global economy may give us a perception on how devastating the recession will be, and how difficult it might be to overcome it.

According to early estimation, major economies were expected to lose at least 2.4% on average of the value of their GDP. This led economists to decrease their 2020 forecasts of global economic growth to 2.4 percent, down from around 3.0 percent. In order to understand this estimation better, global GDP was estimated at around 86.6 trillion U.S. dollars in 2019, this translates to a mere drop of. 0.4% in economic growth amounts to almost 3.5 trillion U.S. dollars lost in economic output. Nevertheless, these estimations were made before covid-19 erupted, and long before the efforts to contain it were implemented. Ever since then, the global economy has suffered from a dramatic decline due to the outbreak, with the actual growth in global GDP for 2020 now confirmed having been -3.5%.

Sector Performances in 2020

Services: The Services sector, incorporating everything from trade, investments, industrial, tourism, and social life, has been one of the worst affected industries in 2020. The reason for its demise is that it relies mainly on face-to-face interactions, and its growth is disproportionate to the length and severity of lockdowns, something the vast majority of people have grown accustomed to in 2020. Nevertheless, not all subsectors of the services sector have been equally affected, and unfortunately aid was not distributed proportionately. In the US for example, while the accommodation and food services industry lost 32% of all jobs in 2020, the financial and insurance sector only lost 0.2% of vocations. Yet, the former only got 8.1% percent of aid distributed – equivalent to $7,800 per job loss from February to April 2020- while the latter obtained a total of $8billion in grants equaling $350,000 per job loss. Other extremes were the real estate sector totaling 91,300$ in funding per job loss and the arts and entertainment sector obtaining $8,000 per job loss.

| Industry | Jobs Lost (%) | Grants (%) |

| Finance & Insurance Services | 0.2 | 2.3 |

| Real Estate Services | 1.1 | 3.0 |

| Information Services | 1.2 | 1.8 |

| Professional, scientific & technical Services | 2.5 | 12.7 |

| Arts & Entertainment | 6.3 | 1.6 |

| Accommodation & food services | 31.8 | 8.1 |

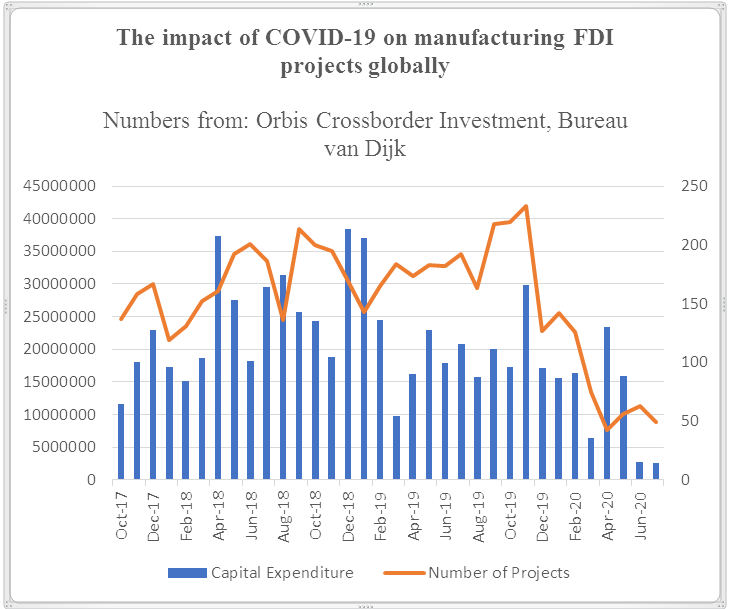

Manufacturing: While the manufacturing sector also suffered, the sector was relatively better off during 2020 than services. In fact, 94% of all manufacturing plants were operational during peak pandemic times, with 56% of them operating at full-operational capacity and 44% at partial capacity. Nevertheless, global Foreign Direct Investment in the manufacturing service sharply decreased as the pandemic caused investors to become more risk averse. In general, global FDI decreased from a high of $29,823 million for a total of 233 projects in the month of November 2019 to a low of $2,513 million across 49 projects in July 2020.

IT and Communications: As expected, the IT and communications sector had one of its best years in 2020 in terms of global adoption. From the consumer side, online shopping has increased by 15%. Amazon, an the largest IT-based company roughly doubled its entire workforce by adding 400,000 extra jobs. As for corporate adoption, a study by McKinsey and Company claims that “funding for digital initiatives has increased more than anything else—more than increases in costs, the number of people in technology roles, and the number of customers”. In fact, that same study also concluded that the pandemic has led to the percentage of North American digital consumers to rise by 58%.

Oil and Transportation: Air-travel’s decrease of 60% owing to the pandemic has left the airline industry with losses amounting to $370billion. With aviation being the primary consumer of 7.8% of all total oil consumption worldwide, it is then no surprise to see that the commodity price of oil has fallen by -32.7% in the year of 2020, with a portion of that fall reflecting the decrease in oil demand by manufacturing plants as well.

Global Trends 2020

As the pandemic primarily emerged, imposing increasing and surging human costs worldwide, the global economy was projected to decline by 3% in 2020. This is much worse than what had occurred during the 2008-2009 financial crisis. These numbers were preliminary and were based on the assumption that pandemic was supposed to fade in the second half of 2020 and lockdown measures would eventually unwound. Additionally, the global economy was projected to grow by 5.8% in 2021 as the economic activity returns to its normal pace. However, the reality is that the pandemic had a more negative impact in the first half of 2020 than anticipated and the recovery is predicted to be slower than previously estimated. Secondary estimations have predicted a further decline of growth projected at -4.9%, and a global growth of 5.4% in 2021. The stricter the lockdown measures, and the wider spread of the pandemic, the greater the uncertainty around this forecast. The baseline of the projection rests on key assumptions about the fallout from the pandemic. Specifically, among emerging markets, the first quarter GDP was worse than expected, with a catastrophic hit to the global labor market, a contraction in a global trade and weaker inflation. Nevertheless, while the impact is different across the different sectors and different regions.

Recovery: Sectors Projections

Sectors:

Services: The recovery of the service sector will depend largely on how effective vaccines are in achieving herd immunity, and how fast they are distributed. If vaccines are distributed in bulk and lockdown measures begin to fade, advanced economies would reach herd immunity by mid 2021, and the services sector would directly rebound. There is also an opportunity for developing economies to permanently shift to a more digitalized service sector, as the pandemic has given them the opportunity to familiarize themselves with appropriate technology, which has vastly increased growth in services by complementing traditional means of work.

Manufacturing: For 2021 and beyond, Covid-19 might have been a blessing in disguise for the manufacturing sector. Yes, output has vastly decreased as global trade and supply chains took a grand hit, forcing many manufacturing companies to either exit the industry completely or temporarily suspend operations. But for those that survived, 96% of manufacturing CEO’s have claimed that the pandemic has sped up their digitization plans, thus allowing them to increase outputs for a lower cost. And with the promise of better 5G networks, AI systems, and virtual reality models, the future of this industry seems promising.

IT and Communications: This sector can be seen as a hero of the pandemic. From virus heat maps and virtual clinics, to online learning and corporate meetings, the IT and communications sector helped humanity endure lengthy economic shutdowns. As for the future, the world has now embraced technology more than ever before and is not going to look back. Automated manufacturing plants and AI service robots are both set to change the manufacturing and service sectors in the near future, causing various low-to-medium skilled jobs to become obsolete while high-skilled opportunities increase.

Oil and Transportation: 2021 doesn’t look like the year in which oil rebounds, in fact, oil prices might take as long as 2023 to go back to pre-pandemic levels. This pessimistic outlook is related to the transportation sector, with new strains of the virus emerging and vaccines set to take a long time before being properly distributed in developing nations, meaning that the travel industry, and overall demand for oil, will remain stagnant. Additionally, OPEC+ producers have already agreed to increase oil output by 500,000 barrels per day at the beginning of 2021, with further discussions to possibly re-increase output by an extra 500,000 barrels per day beginning 1st of February 2021. If these increases prove to be too impulsive, oil prices could even see a further decrease in 2021.

Anticipated Growth by Regions 2021:

MENA Region:

In 2020, and after being forecasted to grow by 2.6 percentage points, the MENA region’s growth instead contracted by 5.2%. Due to the duality of the Covid-19 pandemic and oil crisis, oil exporting countries in MENA suffered incredible losses while the gains of oil-importing economies were offset by the hit of the tourism sector and the substantial decrease in remittances. In fact, output loss in the region is expected to exceed $230 billion. And as countries have to rely on expansionary monetary and fiscal policies to support struggling businesses, public debt in the region is expected to reach 58% of GDP in 2022, up from 45% in 2019. According to data from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, trade is also projected to have fallen by 40% in the region in 2020. In 2021 though, The MENA region is expected to bounce back strongly with a growth percentage of 3.2%, with all economies in the region expected to grow in some capacity (except for Lebanon which is expected to contract by a further 6.4%). Yet after the initial rebound, growth in the region is expected to heavily stagnate owing to the following risks.

- Weak Fiscal and Health Care systems

- Having populations at a constant risk of displacement (eg: Syria)

- Increase in short-term inequality owing to the oil sector being the first to recover

- Increased US-Iran tensions

- Conflicts in Libya and Syria exacerbating and Yemen’s Peace talk imploding

- Delays in the formation of governments in many MENA countries

Europe

In Europe, real GDP growth is projected to have decreased by 7.4% in 2020, more than during the global financial crisis. The impact was felt most by the region’s more advanced economies, including Spain (-12.8%), Italy (-10.6%), France (-9.8%), and the United Kingdom (-9.8%). These contractions were mostly caused by the drop in demand, exports, and tourism, as well as the volatility faced in the financial markets and supply chains. Nonetheless, the situation could have been more dire still if not for the economic support that governments showed. Job-subsidizing policies, for example, are thought to have preserved a minimum of 54million jobs and kept demand relatively higher. In 2021, Europe is expected to start its recovery with a forecasted growth of 3.6% founded by enhanced covid-19 management and preliminary vaccine rollout. In the coming years, it is also advised that Europe re-focus its policies on products instead of people, aiming to solve the continent’s long-standing problems of increasing income concentration, low productivity growth, and the short-term struggles in shifting to more climate-friendly corporate standards. The risks that might stand in the way of such progress include:

- Insolvency of firms leading to a weakened banking sector at best and a financial crisis at worst

- The loss of global chain partnerships

- Brexit dampening trade within Europe

- The continuance of the current drought affecting large parts of Eastern Europe

Asia

Remarkably, Asia was perhaps the continent that most effectively handled the pandemic. On average, Asian economies were the fastest to enforce strict lockdown measures, closing after an average of five days following an outbreak. These measures proved fruitful, as Asia is set to contract only 2.2% in 2020 and then grow by 6.9% in 2021. In fact, some Asian economies actually grew in 2020, most notably China (1.9%) and Vietnam (1.6%). What is perhaps even more astounding that despite the growth in 2020, China is still set to grow by a further 8.2% in 2021, making it the world’s most resilient economy during the pandemic. In fact, China is also Asia’s most relatively open economy, with schools and the industrial plants fully open, retail and services open with restrictions, and travel partially open. Quite a few lessons can be learned by the way most Asian economies mitigated Covid-19, for on average, Asian countries exited lockdown with the fewest new cases, showing that it is better for both overall health and the economy to only ease lockdown once the virus has been suppressed. Asian countries, on average, also had the most testing and tracing percentage in the world, highlighting the importance of government initiative in trying times. Nevertheless, some risks still remain for Asian economies to beware off in 2021 and are the following:

- An escalation in the US-China trade war, and overall tensions between the two political behemoths, could be potentially disruptive to the region’s trade, financial, and technological sectors.

- While Asia was relatively effective in curbing the pandemic, the crises that ensued were disproportionately impacting the most vulnerable classes, with little-to-no government action to prevent the poorest from suffering the largest burden of the costs.

- An expected tightening of monetary policy directly after the pandemic could be extremely risky to small and medium enterprises in particular, and to the overall credit and debt markets in general.

- An increase in regional geopolitical tensions between India and Pakistan, India and China, and the parties involved in the South China Sea dispute, could lead to a race to the bottom.

China

Despite being the pandemic’s pivot, China has become the first and only major economy to recover from the consequences of 2020 and enter 2021 with a rather optimistic outlook. The implementation of stable and “time-sensitive” policy responses has allowed China’s economic growth in the last quarter of 2020 to return to its pre-pandemic levels.

In the first quarter of 2020, China’s growth shrank 6.8%, but it bounced back in the second and third quarters with a rate of 3.2% and 4.9% respectively. This bounce back can be attributed to several strategies, one of them is the reprioritization of macroeconomic objectives, and a focus on enhancing exports, connected to the high demand for medical supplies, equipment and electronics. Factors also include a great deal of investment in infrastructure and real estate. Despite hitting a low in 2020, several experts predict China’s GDP growth will reach 8 to 9 percent in 20201.

US-China Relations: Old vs New Administration

China’s economic pre-pandemic normalization is strongly linked to its tension with the U.S. The US-China trade war was launched back in 2018 with President Trump, when the US trade deficit widened. However, because of the pandemic, there has not been much improvement from the trade war’s retaliatory tariffs. In 2019, the US trade deficit with China decreased by 8.5%, and then increased again by 5.4% in 2020. Currently, it accounts for about 37% of the US total trade deficit. Should China achieve 8% of growth this year, with predicted currency appreciation and domestic inflation, IMF forecasts that the size of China’s economy relative to the US could be higher than 75%. So, it is expected that newly elect president Joe Biden’s stance on China will remain tough. Biden has previously explained that he will not cancel the Trump’s administrational additional tarrifs on China. Also, analysts expect that Biden might seek collaboration the U.S.’s well known allies to jointly contain China.

USA

In 2020, the United States faced a truly tough year. Even though its economic contraction of 4.3% tracks with that of the rest of the world (4.4%), the U.S. faced one of the worst health scenarios as it had over 20% of world-wide Covid-19 deaths even though it accounts for roughly 4.25% of world population. Prior to the pandemic, Trump’s economy was faring quite spectacularly, with unemployment reaching a 50-year low and inflation below the target of 2%, but it soon came crashing. During the second quarter of the year, real GDP sharply fell by a tremendous 31.4% while unemployment levels reached 14.7%. But what is perhaps most astonishing is the financial markets’ nonalignment with the economic reality. Even though U.S. stocks dipped during the beginning of the pandemic, they have now peaked and are estimated to be a record-breaking 83.8% overvalued. In comparison, stocks were only 49% overvalued during the Tech Bubble in 2000. Yet, the U.S. economy is still expected to grow by 3.5% in 2021, which is 0.5% lower than what was previously projected. Nonetheless, the following risks make it clear that while U.S. GDP might fully recover, welfare will take a longer time to do so:

- The U.S.A. is projected to have a K-shaped recovery. Meaning that like the letter “K” that diverges in its strokes, so will the fortune of different classes in the U.S. economy. The rich are projected to get even richer while the poor still poorer.

- The “K” economic recovery will also prevalent be in the job market. Sectors such as banking, telecommunications, and real estate now offer wages at levels 50% higher than before the pandemic while jobs in the leisure and hospitality sectors suffer from lower wages and a loss of 25% of employment.

- Increased divide between the U.S. population’s political affiliations might cause serious social skirmishes, not unlike the recent Trumpian storming of the capitol

- Potentially dangerous escalations in the conflicts between the U.S. and North Korea, Iran, and China.

U.A.E.

2020 has been a mixed year for the United Arab Emirates. With 30% of its GDP coming from gas and oil extracts, there is no wonder that the commodity’s fall in price had damaging effects on the economy, with oil output in Q3 reaching an almost decade low. As Covid-19 cases recorded new daily highs, the U.A.E government has done everything in its power to avoid extreme lockdown measures, including authorizing the emergency use of Chinese-owned company Sinopham’s vaccines, which have so far proven to be effective in the first two clinical trials. Whilst the economy is set to contract by 6% in 2020, U.A.E. officials can take comfort in the resilience of their non-oil private sector, which has reached a 16-month PMI high. This was not at all a stroke of luck but rather a result of careful planning and decision making.

Domestic markets: The Central Bank of the United Arab Emirates announced specific policies to deliberately ensure the survival of local businesses. It launched the Comprehensive Economic Support Scheme, with a goal to use a total of $27.23 billion to relieve private businesses and retail consumers of interest accumulated on outstanding loans, which is meant to act as a monetary stimulus to both strengthen supply and demand in the economy. Fiscal policies were also adopted, with the Central Bank launching the Targeted Economic Support Scheme and the UAE Cabinet declaring a further $4.36 billion stimulus package. The policies’ main objective being the support of domestic companies by cutting the cost of doing business and investing heavily in infrastructure projects. U.A.E is already one of the most diversified oil-exporting economies, and the country plans to further strengthen more non-oil related sectors in a bid to shift to a more modernized strategy. The financial sector will be pivotal in determining the success of such plans with the U.A.E counting on their easygoing lines of credit to fund projects mounting to a total value of $868 billion. $672 billion of the aforementioned valuation are pipeline projects of which $417.7billion are construction related. Moreover, the U.A.E also aims to revolutionize its travel and health care industries through heavy digitization. Country officials aim to continue introducing and expanding AI systems into these sectors to improve productivity, facilitate data collection and redistribution, and reduce human error. The U.A.E has already tested these AI models in their National Unified Medical Record, an AI central database in Dubai that was successful in redefining the region’s health care industry, and that is now being implemented nation-wide

Cross-border operations: The UAE’s recent success in negotiating an agreement with Israel to build a pipeline in Ashkelon is projected to substantially increase Emirati oil demand as the pipeline will be used to transport oil into Europe. On the 6th of January 2021, the U.A.E and Qatar agreed to fully reestablish diplomatic ties, which were severed on the 5th of June 2017 as part of the Qatar diplomatic crisis. Consequently, the U.A.E should see first quarter boosts to its trade and travel sectors. Lastly, it is predicted that the UAE will find itself largely unaffected by regional political instability, despite heavy Iranian tensions. As for domestic politics, the system is also expected to prove itself stable with a possible transfer of power from Abu Dhabi ruler His Excellency Khalifa bin Zayad Al Nahyan to Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan expected to flow smoothly if the former’s health issues are to further deteriorate.

Political reality: In 2021, UAE’s economy is set for a recovery of 2.5% in real GDP, as well as a much-anticipated political reform. His Highness Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum has announced that the U.A.E will alter, merge, and change a number of governmental bodies in a bid to facilitate future governmental reforms by creating a more “agile, flexible, and speedy government”.

Possible Risks: Economists have been predicting a harsh expat exodus facing the UAE, with the UAE losing approximately 10% of its residents owing to a loss of 900,000 jobs. Due to expats having no welfare schemes and no permanent-citizenship routes, the loss of jobs has left most of them unable to bear the burden of the pandemic and contemplating a move back to their original countries. Nevertheless, the UAE once again acted swiftly to mitigate the effects of such a disaster by passing a decree that allows expats to use their native laws instead of the Sharia when dealing with personal affairs. It has also launched a virtual visa scheme that allows working professionals to relocate to Dubai and enjoy access to unfettered services, and started a retirement program for foreigners over 55, all in the hopes of encouraging foreign labor. On the supply side, Dubai has commenced an e-commerce platform called the Virtual Company License that allows businesses from all over the globe to freely explore the UAE market, with the platform set to attract over 100,000 companies in the near future. However, all of the aforementioned schemes, stimuli, and policies to protect the economy from the effects of the pandemic may backfire. As a result of these generous measures, Dubai’s governmental debt is estimated to have reached 77% of GDP ($80billion), and if we were to add government-related entity debt to that number, ratings agency S&P predicts that total debt is an astronomical 148% of GDP($153.8 billion).

To summarize, the UAE will start recovering in 2021 but future growth might slow down as a result of Dubai’s growing debt and the possibility of an Abu Dhabi bail-out similar to the one in 2009. A shift to increased diversification and fast vaccine rollout has helped the economy resist a further contraction of GDP but oil still remains fundamental. As such, lower-for-longer commodity prices are set to also contribute to the economy’s slow growth, even if the U.A.E does manage to capture a larger share of the European oil market.

Other Countries worth mentioning

- Turkey: Turkey’s case in 2020 is an interesting one to say the least. Even though it contracted by 3.8%, and even though its Lira was heavily devalued when measured against the US dollar, Turkey still managed to avoid a bigger contraction as a result of intense policies oriented towards increasing credit. Nevertheless, Turkish businesses still suffered from the pandemic, especially those affiliated with the touristic sector and those that had limited solvency before the currency devaluation. And even though Turkey’s policies were an overall success, the nations’ restricted monetary reality left it incapable of carrying out all of the procedures it had originally planned.

- KSA: In comparison, Saudi Arabia has had a relatively less rosy year. Stringent lockdowns coupled with a decrease in oil prices throughout 2020 has left the economy in shambles, with a growth rate of -5.4%. While some investors are optimistic that KSA’s economy is set for a rebound in 2021, others are warry seeing that growth in Saudi Arabia will largely depend on the recovery of global demand and the price of oil, which is expected to face another dip. The pandemic may also leave quite a lasting scar in the economy as the instability of financial markets and the country’s rising public debt might hamper the KSA’s plans to increase economic diversification in the near future. Still, save an exogenous shock or increased non-compliance by OPEC+ countries, KSA’s economy is set to grow by 3.1% in 2021.

- Russia: Following its worst recession since World War II, the Russian economy is set to contract by 3.6% in 2020, with the hardest hit industries being retail, manufacturing, and construction. The pandemic has had a spillover effect on most Russian livelihoods, with the shrinking of businesses estimated to thrust 130 million people into extreme poverty by 2021. The Russian government, however, acted swiftly and have put in place several countercyclical fiscal policies raging from substantial macro-monetary support for struggling corporations to targeted social safety net policies meant to alleviate the burden of carried by the most vulnerable. Nonetheless, Russia was still helpless to combat certain issues, such as disrupted trade with the EURO zone -its largest trading partner- due to the pandemic’s effect on global value chains. In 2021, Russia is expected to start a strong rebound of 3%, followed by a complete recovery in 2022 when it is estimated to grow by a further 3.9%. Russia’s relative ease in rebounding from this pandemic lies in its still largely unfulfilled potential, with a gradual shift towards more technological driven manufacturing the basis for Russia’s expansion in the coming few years.

Global Trends:

-

Trade

We know that trade tends to be volatile and extremely susceptible to such crises (Bussière et al. 2013). In fact, total trade has decreased by 18.5% this year, the “steepest drop on record”, according to WTO Director General Roberto Azevêdo. Causes for such a deep contraction are various. Covid-19’s impact on travel has adversely affected the tourism sector, which is in turn responsible for the consumption of approximately 6.5% of world-wide goods and services. Moreover, the closure of borders between countries, accompanied by stricter import inspections, have resulted in an unwanted strain on the production and delivery of durable goods, most notably on electrical and automotive industries. As delivery time increases, most businesses that rely on day-to-day transactions have suffered from an increase in costs, and the air freight industry has been barely avoiding total ruin. Finally, disturbances in the credit market has had a rippling effect throughout trading economies, and as such, many agreements have fallen through. While the growth of global trade is imminent in 2021, complete recovery is less so. As borders gradually start the reopening process, airlines will start refilling their seats, and manufacturers will go back stocking their inventories. Nonetheless, trade’s recovery path depends on both overall confidence level, which will take time to go back to pre-pandemic levels, and the time needed to replace firms that have either contracted or shutdown due to low demand. In short, global trade should expect nothing more than a slow, L-shaped recovery

-

Food Crisis

The corona virus could not have come at a worse time for the 2030 zero hunger goal. With global food chains being hampered by the pandemic and job losses caused by economic tolls leading to more poverty, a large percent of the population will become food deprived in the coming years. The most vulnerable countries so far are Afghanistan, Burkina Faso Cameroon, The Central African Republic, Congo, Ethiopia, Haiti, Lebanon, Mali, Mozambique, Niger, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Venezuela, Yemen and Zimbabwe. The UN estimates this crisis to be the worst food-related calamity in half a century. In fact, more people are now projected to die from Covid-associated food shortages than from the actual virus itself.

A potential debt crisis: Dangers of the Fourth Wave of Debt

The global recession triggered by Covid-19, along with the economic policy response, have generated a rise in debt levels, especially in emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs). Pre-pandemic, however, there has been an increasing concern about a “fourth wave” of debt accumulation, specifically in these economies, that can spark the possibility of financial crisis. This pandemic merely added to the risks and consequences of this fourth wave by intensifying this crisis. In 2019, global debt has increased to 230, an alltime high, and government debt to a record of 83% of GDP. In EMDEs specifically, total debt reached 176 percent of GDP and government debt is expected to rise by 9% of GDP in 2020.

As a result of substantial financial stimuli, accrued interest on loans, and weaker capital flows, world debt has risen to 365% of global GDP, growing by more than $15 trillion in 2020 alone. Even though the global financial system is less inter-connected today than pre-2008 levels, six countries (Argentina, Belize, Ecuador, Suriname, Lebanon, and Zambia) defaulting in 2020, along with the IMF disbursing aid to 81 nations, has left a fiscal strain that could soon burst. The G20 has already identified this potential risk and has tried to address it by creating a “Common Framework” to oversee the management of a debt relief system but has so far been undermined by the U.S.’ unwillingness to endorse further IMF resource support.

Concluding Remarks

2021 holds a great many uncertainties, challenges, and confusion as policymakers have to decide on whether or not to pursue recovery-inducing expansionary stimuli at a risk of ever-increasing debt and an imploding financial system. And while advanced economies generally have the means to induce economic activity, international organizations fear that this pandemic will hurt emerging countries’ prospects for decades to come. Not only will this crisis roll-back years of hard-work in reducing poverty, but the overall impact on welfare cannot be measured. Research has shown that a great number of college graduates that do not immediately find a job will suffer from related consequences for the rest of their lives, as evident by Japan’s lost generation where limited job opportunities between 1991 and 2003 has caused 3.4million 40 to 50 year-olds to remain jobless today. Prolonged mental health issues caused by either the health or economic toll of the pandemic is also something we find difficult to measure and is an unaccounted welfare cost of the virus. If all goes according to pre-set plans and no new crises emerge, the global economy is set to grow back by 5.2% in 2021 in real GDP. Alternatively, this number, along with actual welfare, could even prove to be too low if the global community was to cooperate and come up with collaborative solutions. Making sure that vaccines are manufactured and distributed swiftly, providing a safety cushions for the most vulnerable classes, sharing expertise on the navigation of Covid-19 induced calamities, and setting up an international framework to build up global resiliency to future crises through sustainable growth will not only allow for faster world-wide recovery, but might also prevent future disaster scenarios by building global ties able to withstand pressure.