Shaping a Transparent Future: The AACI’s Mission to Elevate Ethical Banking

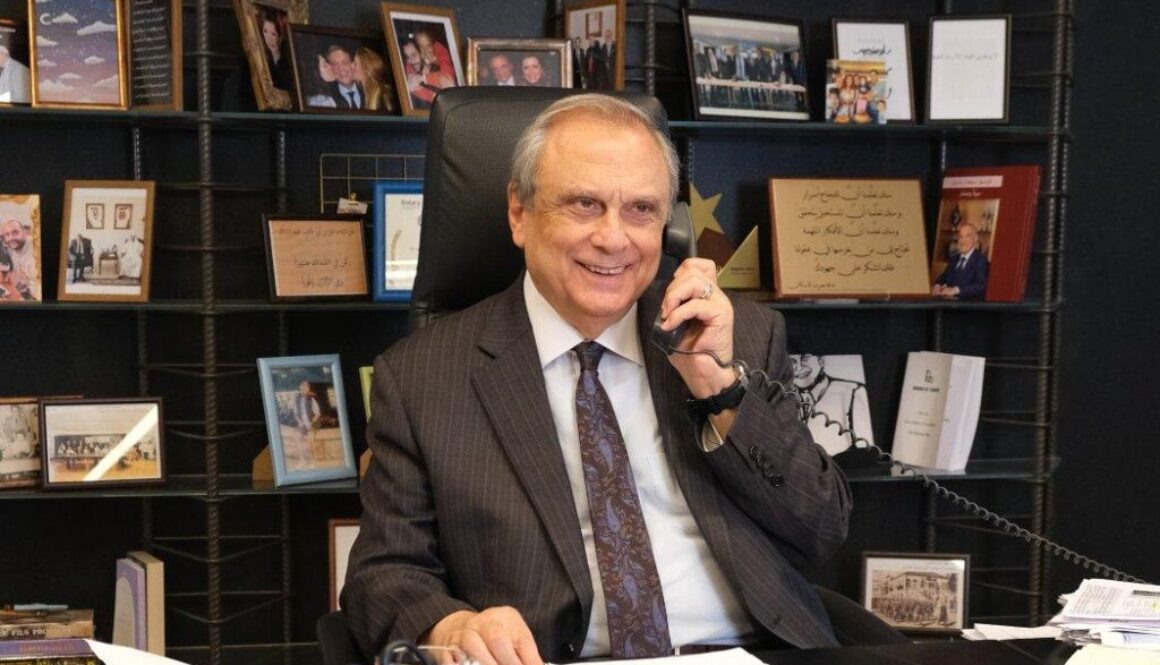

Interview with Mr. Mike Masoud, Anti-Corruption Expert at the American Anti-Corruption Institute (AACI)

1. Overview of The American Anti-Corruption Institute (AACI)

The American Anti-Corruption Institute (AACI) is a leading global organization dedicated to empowering board members, executive management, and managers—collectively referred to as decision-makers—with the cutting-edge anti-corruption knowledge and skills necessary to prevent and combat corruption and fraud. Established with a mission to equip decision-makers across various sectors, including banking, with the tools to effectively identify, manage, and mitigate corruption risks, The AACI offers a range of anti-corruption certifications. We aim to ensure that the tone at the top is proper and proactive in safeguarding organizations from the damaging effects of corruption. The Institute’s flagship programs include the Certified Anti- Corruption Manager (CACM), the Certified Anti-Corruption Fellow (CACF), the Certified Anti- Corruption Expert Manager (CACEM), and the Certified Anti-Corruption Entity (CACE), among others. These certifications serve to cultivate an informed, ethical, and proactive workforce capable of making sound decisions in the fight against corruption.

2. What does the recent Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) signed between The AACTI, the Union of Arab Banks (UAB), and Tomorrow’s Advice (TA) mean for the future of anti-corruption efforts in the MENA region?

The MOU signed on August 22, 2024, represents a significant step forward in our collective efforts to institutionalize anti-corruption initiatives across the banking sector in the MENA region. This partnership with the Union of Arab Banks (UAB) and Tomorrow’s Advice (TA) aims to advance anti-corruption learning and certification programs for UAB members. By promoting the culture of anti-corruption and disseminating knowledge about The AACI’s Ten Principles of Fighting Corruption, we seek to empower the banking sector with the necessary tools to prevent corruption proactively.

The MOU underscores the importance of collaboration between industry leaders, governance bodies, and institutions in creating a transparent, ethical banking environment. This partnership will enhance the integrity of the sector, fostering a stronger, more resilient financial system that aligns with global standards of anti-corruption and integrity.

3. How does this partnership with UAB and TA align with The AACI’s mission to promote integrity and transparency in the banking sector?

Our mission at The AACI has always been to empower decision-makers with the knowledge and skills to proactively prevent corruption and fraud. This partnership with the UAB is a natural extension of that mission, as the Union represents 360 member banks and financial institutions across the Arab League member states, Europe, and Turkey.

Through the MOU, we are working together to promote transparency, independence, and competence across the banking sector. By implementing anti-corruption certification programs and disseminating The AACI’s Ten Principles of Fighting Corruption, we aim to bolster the ethical foundations of the banking industry and ensure that it remains a trusted institution for sustainable economic growth and stability.

4. Why is the banking sector critical in the fight against corruption, particularly in the MENA region?

The banking sector plays a pivotal role in economic stability and growth, which makes it a critical player in the fight against corruption. In the MENA region, where corruption risks can be heightened due to complex political and economic dynamics, banks have a unique responsibility to safeguard the integrity of financial transactions and prevent the flow of illicit funds.

By fostering a culture of integrity, anti-corruption, and compliance with the relevant laws, rules, and regulations, we ensure that financial institutions remain accountable to their stakeholders, customers, and regulators. This partnership with the UAB helps to institutionalize anti-corruption practices within banking operations, enhancing both regional and global efforts to combat financial crimes such as money laundering and terrorism financing.

5. How do The AACI’s anti-corruption certification programs, like the CACM, play a role in promoting integrity within financial institutions?

The Certified Anti-Corruption Manager (CACM) and other certifications of The AACI are designed to equip professionals in the banking sector with the knowledge and tools to tackle corruption effectively. By addressing the CACM’s core areas of anti-corruption, internal control, governance, anti-money laundering, auditing and accounting for decision makers, Blockchain and AI, the United Nations Convention Against Corruption, the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention, Financial Actions Task Recommendations, and risk management, these programs empower managers and executives to implement robust anti-corruption frameworks in their organizations.

With the increasing emphasis on anti-corruption compliance from both regulators and the public, certifications like the CACM provide professionals with the skills necessary to meet and exceed these expectations. This is particularly important in regions like MENA, where the regulatory landscape is evolving and financial institutions must stay ahead of emerging risks and compliance requirements.

6. What impact do you foresee from this partnership on the sustainable development 4% goals (SDGs) and the broader economic stability in the MENA region?

This partnership has a direct alignment with the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly Goal 16: Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions. By promoting anti-corruption learning, integrity, and transparency within the banking sector, we are contributing to the creation of more stable, accountable, and transparent financial systems in the MENA region.

The long-term impact of this initiative will be felt not just in the banking sector but in the broader economy as well. A transparent, ethical financial system fosters investor confidence, supports sustainable economic growth, and strengthens the region’s ability to attract foreign investment. Ultimately, this partnership represents a vital contribution to both regional and global efforts to foster economic stability and prosperity.

7. How does the banking sector’s anti-corruption strategy align with national efforts to combat corruption?

The banking sector is a critical player in national anti-corruption efforts due to its role as a cornerstone of the economy and its responsibility to ensure the integrity of financial transactions. For an anti-corruption strategy to be effective, it must align with the broader national anti- corruption strategy.

At The AACI, we emphasize that a bank’s anti-corruption strategy should be designed, implemented, and evaluated in a way that supports not only the bank’s internal goals but also those of the broader banking sector and the country. This alignment fosters collaboration, ensures consistency in combating corruption across sectors, and strengthens national resilience against corruption. The AACT’s certification programs, including the CACM, equip banking professionals with the expertise to develop and manage strategies that contribute to this unified effort.

8. Why is addressing conflicts of interest essential in the fight against corruption within the banking industry?

Conflicts of interest are a corruption risk in the banking sector and can significantly undermine its integrity if left unchecked. They may arise in various forms, such as unethical decision- making or favoritism, which can ultimately lead to corrupt practices.

The AACI’s anti-corruption certification programs, especially the CACM, place significant emphasis on understanding the nature of conflicts of interest, identifying their sources, and implementing measures to mitigate their risks. By educating banking professionals on these issues, we ensure they are equipped to recognize and address conflicts of interest before they escalate into corruption. This proactive approach strengthens governance and fosters trust among stakeholders.

9. What role does institutional integrity play in fostering an ethical banking environment?

Institutional integrity refers to an organization’s adherence to the Ten Principles of Fighting Corruption and Standards on Fighting Corruption (SFCs) in its interactions with stakeholders, distinguishing it from the concept of individual integrity. For banks, institutional integrity is fundamental in building trust, maintaining a solid reputation, and ensuring sustainable operations.

The AACI champions the importance of institutional integrity through initiatives like the Certified Anti-Corruption Entity (CACE) program. This certification demonstrates an entity’s commitment to combating corruption and fraud while fostering a culture of transparency and accountability. Moreover, banks with more CACM-certified professionals are better positioned to enhance their institutional integrity, as these professionals bring expertise in designing and implementing effective anti-corruption measures.

10. How can whistleblowing strengthen a bank’s anti-corruption strategy?

Whistleblowing is one of the most effective methods for detecting fraud and corruption. Research shows that over 50% of fraud and corruption cases are uncovered through tips provided by employees, customers, or other stakeholders.

An effective anti-corruption strategy for banks must include whistleblowing as an integral component. The AACI’s CACM certification dedicates a comprehensive unit to the topic of whistleblowing, covering its nature, methods, and policy design. By implementing robust whistleblowing mechanisms, banks can deter, prevent, and detect corruption more effectively while promoting a culture of accountability and transparency. Encouraging and protecting whistleblowers ensures that concerns are raised without fear of retaliation, strengthening the organization’s defenses against corruption.

Conclusion

The signing of this MOU marks a turning point in our efforts to combat corruption and promote transparency within the banking sector. By joining forces with the Union of Arab Banks and Tomorrow’s Advice, The AACI is committed to ensuring that anti-corruption principles are firmly embedded in the fabric of the banking industry, not just in MENA but globally. Through initiatives like the CACM certification and the dissemination of best practices, we are empowering professionals and organizations to take proactive steps in safeguarding the future of our financial systems.

Press Release – The American Anti-Corruption Institute (AACI) and the Union of Arab Banks (UAB) sign a Memorandum of Understanding to Promote Anti-Corruption and Integrity

The American Anti-Corruption Institute (AACI) proudly announces the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the Union of Arab Banks (UAB) and Tomorrow’s Advice Global s.a.l. offshore Lebanon (TA Global) alongside Tomorrow’s Advice s.a.r.l. (TA). This significant agreement was formalized on August 22, 2024, during the “Annual Forum of Combatting Money Laundering and Terrorism Financing: The Repercussions of Cash Economy on the Banking Sector” at the Phoenicia Hotel Beirut, Lebanon. The conference was held under the auspices of the Acting Governor of the Central Bank of Lebanon and Head of the Special Investigation Commission in Lebanon, Dr. Wassim Mansouri.

The MOU was signed by Dr. Wissam H. Fattouh, Secretary General of the UAB and Mr. Mike Masoud, Senior Director of the Middle East and Africa at The AACI, , and Mrs. Gina J. Chammas, CACM, Founding Partner of TA Global and TA, and Senior Adviser of The AACI in MENA. The signing ceremony was attended by Retired Brigadier-General PSC, Hassan Jouni, PhD, CACM, Advisor of The AACI in the MENA region.

The forum and the ceremony were attended by esteemed guests, CACMs members of The AACI, and professionals in related fields, highlighting the importance and far-reaching impact of this partnership.

The MOU outlines a collaborative effort to advance anti-corruption learning and certification programs for members and stakeholders of the Union of Arab Banks and the banking sector under the UAB’s jurisdiction. The parties have committed to a partnership that seeks to bolster the integrity of the banking sector by equipping its members with essential anti-corruption knowledge and tools. The Union of Arab Banks shall promote the culture of anti-corruption and disseminate knowledge about the Ten Principles of Fighting Corruption promulgated by The American Anti-Corruption Institute (AACT) to its members throughout its territory.

This MOU represents a pivotal step forward in the ongoing efforts to institutionalize corruption prevention, integrity, and transparency in the banking sector in particular, and in sustainable economic development in general.

About The American Anti-Corruption Institute (AACI): The AACI (theaaci.net) is a pioneering organization dedicated to empowering executive management and governance bodies with the knowledge and skills necessary to prevent fraud and corruption proactively. Through its premier anti-corruption certification programs for individuals and entities, including the Certified Anti-Corruption Manager (CACM) and Certified Anti-Corruption Entity (CACE), The AACI fosters institutional change and assesses corruption risks, guided by its Ten Principles and Standards on Fighting Corruption, and promoting transparency, independence, competence, and integrity. The AACI emphasizes corruption prevention as the cornerstone of effective corruption control.

About Tomorrow’s Advice Global s.a.l. offshore Lebanon and Tomorrow’s Advice s.a.r.l.: TA Global and TA are leading management and financial consultancy firms, specializing in strategic advice, development, sustainability, internal control, compliance, governance, and anti-corruption initiatives, particularly within the MENA region.