Investing in Sudan may seem like a weird idea, given that the nation has long been spoiled by civil war and conflict and crippled by sanctions.

Now, the country’s status has transformed; the French government invited Sudan’s political leadership, as well as other world leaders, to an investment conference in Paris on May 17, and there are good reasons to believe it is the right move.

Much has changed in Sudan since April 2019, when a popular uprising toppled President Omar al-Bashir. The country has been removed from the US Department of State’s “Sponsors of Terrorism” list, and it has begun to cooperate with the International Criminal Court (ICC). With the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund both acknowledging Sudan’s progress on economic reforms, the country is moving closer to qualifying for debt relief.

Currently, Sudan is governed by a transitional administration under a power-sharing agreement between the military and a broad civilian coalition of party and civil-society representatives. Though the arrangement is hardly a marriage of love, it offers a model of pragmatism in a region that sorely needs it.

The power-sharing agreement is intended to shepherd Sudan through a 39-month transition period that will end in late 2022, after the launch of a constitutional drafting process and parliamentary, presidential, and regional elections. Against all odds and predictions, the country’s experiment in military-civilian cohabitation has survived for more than a year and a half, owing largely to personal commitments from Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok and the chairman of the Sovereignty Council, General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan.

Emerging from 30 years of autocracy and 65 years of almost continuous civil war would pose a challenge for any new government. In Sudan’s case, the most important step toward peace so far has been the October 2020 Juba Peace Agreement between the government and a wide-ranging group of rebel movements from Darfur and beyond. These groups are now represented in both the Sovereignty Council – which acts as a collective head of state – and in the cabinet. And negotiations with the most relevant party not to have signed on to the agreement, the Abdel Aziz al-Hilu faction of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North, have begun on on May 25.

Moreover, the transitional authorities have made progress in rejoining the international community through the adoption of agreements and treaties such as the Convention Concerning Forced or Compulsory Labor. They are also working diligently to design a federal system that will accommodate the country’s specific political needs (with plans for a major conference on the issue this month). Other important items on the agenda, such as forming a Transitional Legislative Council, are overdue, but it is hoped that they will be taken up soon.

True, hurdles to a lasting peace remain. The Sudanese state and its security institutions are severely understaffed, underequipped, and overwhelmed by the task of coping with unresolved intercommunal conflicts and criminal militias. And the economic challenges are even more daunting.

But this is to be expected in a country that has undergone a revolution and then a pandemic. Economic conditions in the first two years after the revolution included annual inflation above 300%. Under these circumstances, Sudan’s financial situation has deteriorated considerably, such that bread and fuel queues cost household members hours at a time.

Nonetheless, the government has pursued important economic reforms, not least lifting fuel subsidies and floating the currency. It is working closely with the IMF to fulfill conditions for debt relief. With the support of the World Bank and the World Food Programme, the government has launched a cash-transfer program to shield the most vulnerable segments of the population from the effects of economic restructuring.

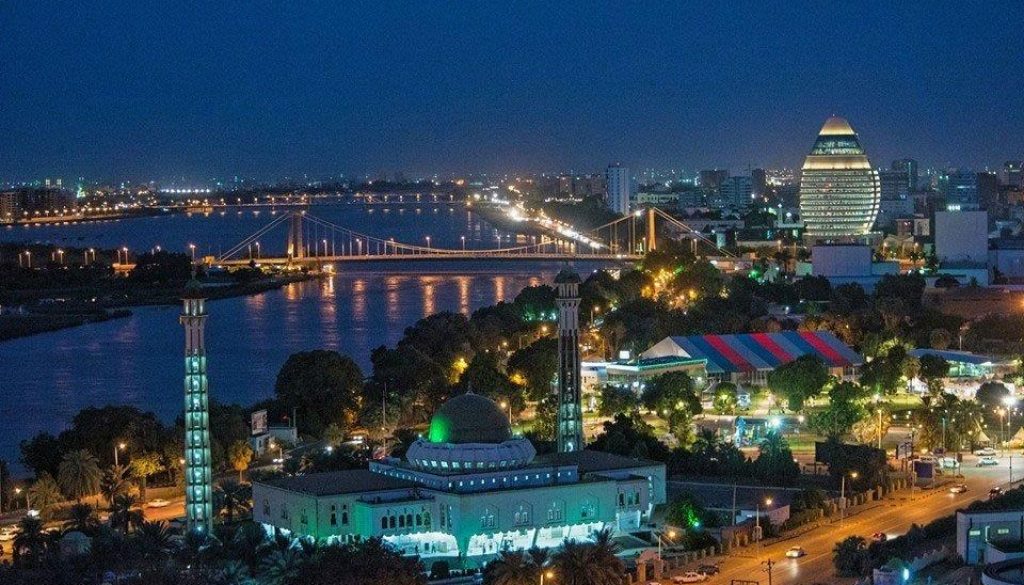

Putting Sudan on the path to sustainable development will require more than humanitarian and development aid. The country desperately needs private investment. With domestic reforms underway to improve Sudan’s investment climate, there are real opportunities emerging in infrastructure, regional connectivity, agriculture, food industries, and electricity.