While the US, China, and other leading economies are on their way to a robust recovery, many others are struggling to return to pre-pandemic GDP levels. In most regions, including Europe and Latin America, the 2020 recession will most likely leave long-lasting scars on both GDP and employment.

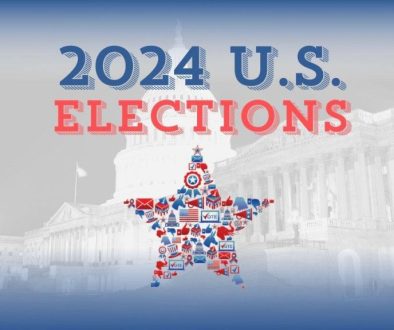

The chances for a swift, uniform rebound from the COVID-19 crisis have dimmed, and the world economy now faces sharply divergent growth prospects. Although the latest update of the Brookings-Financial Times Tracking Indexes for the Global Economic Recovery (TIGER) offers some grounds for optimism, it also raises renewed concerns. Vaccination euphoria has been tempered by slow vaccine rollouts in most countries, while fresh waves of COVID-19 infections are threatening many economies’ growth trajectories.

The US and China are shaping up to be the main drivers of global growth in 2021. Household consumption and business investment have surged in both economies, along with measures of private-sector confidence. Industrial production has rebounded in most countries, firming up commodity prices and international trade. Nonetheless, the US, China, India, Indonesia, and South Korea will probably be the only major economies to exceed pre-pandemic GDP levels by the end of this year. In most other regions, the 2020 recession will most likely leave longer-lasting scars on both GDP and employment.

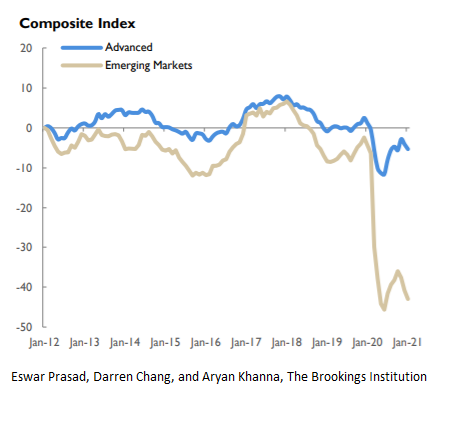

The US economy is poised for a breakout year, as massive fiscal stimulus, loose monetary policies, and pent-up demand translate into rapid GDP growth. Renewed consumer and business confidence has led to generally strong consumption and investment growth, and financial markets have continued to perform well. Even labor market performance has been more encouraging, with 916,000 new jobs added in March, more than double the total for February and the most since last August.

The task for monetary policymakers this year will be to separate phantom inflation (the imminent bounce-back after 2020) from underlying wage and price pressures. The rise in government bond yields – which reflects a combination of better growth prospects, inflation risk, and debt concerns – reflects the challenges that policymakers will face as they try to decipher and manage market expectations. Ideally, any additional stimulus measures will aim to boost aggregate demand and improve long-term productivity simultaneously.

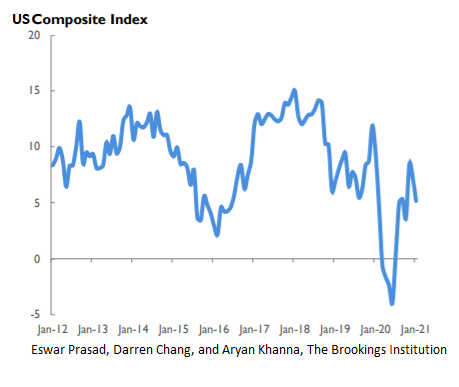

Meanwhile, China’s growth momentum has stayed strong and balanced, with the government turning its attention to medium-term structural issues and the containment of financial-system risks. The recent National People’s Congress backed a renewed focus on rebalancing demand toward household consumption and shifting the sources of output growth toward high-end manufacturing, the services sector, and small and medium-size enterprises.

As such, the Chinese authorities seem to be leaning toward macroeconomic-policy normalization, with some fiscal consolidation and monetary tightening anticipated later in the year. This approach is being accompanied by prudential regulatory measures to manage frothiness in the real-estate sector. While trade tensions with the US appear likely to persist under President Joe Biden’s administration, they no longer seem to be a major factor influencing private-sector sentiment or growth in either country.

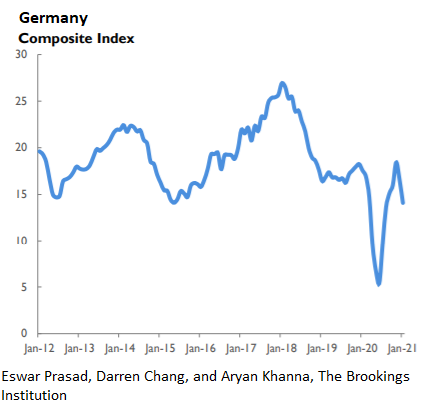

By contrast, European economies, both in the core and periphery of the Eurozone, have been struggling with another COVID-19 wave, floundering vaccination programs, and a lack of policy direction. While industrial production, particularly in Germany, has held up well, much of the Eurozone will probably have to wait until late 2022 before it reaches pre-COVID GDP levels.

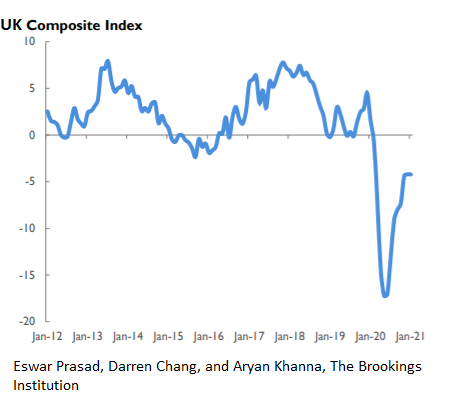

The United Kingdom, which in 2020 faced a double whammy from Brexit and COVID-19, has made good progress on vaccinating its population, thereby improving its growth prospects. Japan’s recovery, however, appears fragile despite extensive stimulus measures, with consumer confidence remaining weak and export growth subdued.

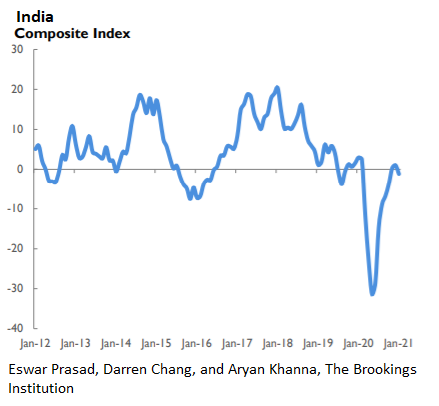

As for emerging markets, there now appear to be multiple economic trajectories – some much better than others. In India, both the manufacturing and services sectors are contributing to a strong rebound. But a resurgence of the coronavirus, rising inflation, and limited fiscal space (owing to high public debt levels) could sap some of this momentum.

For now, the rebound in oil prices has buoyed the prospects of major producers like Nigeria, Russia, and Saudi Arabia. By contrast, Brazil’s economy is tottering, reflecting the virus’s unchecked spread – the result of ineffectual political leadership. Turkey faces similar concerns, but it at least managed to eke out positive growth in 2020.

Following a marked decline during 2020, the US dollar has firmed up in 2021. In tandem with the upward tick in US bond yields, this bodes ill for many emerging markets and other developing economies, particularly those with heavy foreign-currency-debt exposure. Financial market pressures could intensify if divergent growth patterns (with vulnerable economies registering weaker growth) persist through 2021.

The world economy has thus arrived at a pivotal moment. Many countries are grappling with whether to open up their economies despite the continued spread of the virus, and whether to unleash additional macroeconomic stimulus, which could expose them to an unfavorable tradeoff between short-term benefits and longer-term vulnerabilities. Uncertainties are rife, the stakes are high, and indecisive policymaking would hurt consumer and business confidence in the weaker economies, adding to economic strains.

The recipe for a strong and durable recovery remains the same: resolute measures to control the virus, coupled with balanced monetary and fiscal stimulus and policies that both support demand and improve productivity. In economies that are recovering strongly, it would be premature to ease up in either dimension; elsewhere, policymakers will need to redouble their efforts in both.