By S.A.Mansour

The primary key element of any economy in the world is based on the force of its labor markets. Egypt became a center of view for investors and an important digital network among its viewers. Giza and Cairo is located on the border of Nile River in North Africa, from long time, Egyptians crafted the history of the famous Pharaoh civilization and cultures. They showed a tremendous energy of its labor force, and dedication in achieving an accurate work by building pyramids and a 3000 years of developed civilization, where the water is the essential resource of human labours to exercise their tasks in agricultural, industrial, and construction activities.

Egypt’s economy depends on agriculture, petroleum, natural gas, media and tourism; there are also more than three million Egyptians working abroad. A rapidly growing population continue to overtax resources and stress the economy. Cairo accounts for 11% of Egypt’s population and 22% of its economy (PPP), where the majority of the nation’s commerce is generated (Real estate, universities, hospitals, hotels, and media center and film studios).

Government has invested also in communications and infrastructure. Egypt produces its own energy based on coal, oil, natural gas and hydro power, and it has been a net oil and natural gas importer since 2008. Although one of the main obstacles still facing the Egyptian economy is the limited wealth to the average population, higher prices of basic goods, while standards of living or purchasing power remains poor.

Egypt’s labor market comprises of 28.9 million people (26.6 million employed and 2.3 million unemployed). Density is considerably very high and concentrated in Cairo which is 3250 habitat per Km2. Unemployment witnessed four periods of economic recessions and downturn in supply and demand on its labor. And recently, in 2019, the pandemic crisis of Corona Virus slowed down the economy and had a direct impact on the labor market. In the other hand, the pandemic has led to a shift to a new labor era, such as working remotely, creating entrepreneurs, and adopting new technologies. But, Egypt and other Arab countries was not ready to make this labor shift and economic adjustment in order to adjust with the pandemic; while other developed nations was able to maintain the economy and the labor markets. During recession, the national losses were felt mainly by the poor. Over one-quarter (25.2%) of Egyptian households lives under the absolute poverty line, and 4.8% of households live under the food poverty line.

Egypt progressed continuously during the past years to a steady and stable economy with an economic growth in parallel lines within most of its sectors, especially in construction, financial services and technology, nominal GDP reached 363 billion dollars in 2020 equivalent to a GDP per capital of 3560 US dollars.

The Egyptian economy suffered from more than two major events in last 30 years; the most recent, unemployment started to rise due to the political instability following the 25 January 2011 revolution. Egypt has experienced a fall in both foreign investment and tourism revenues, followed by a 60% drop in foreign exchange reserves, a 3% drop in growth, and a rapid devaluation of the Egyptian pound. Unemployment rates reached their peak with the highest rate of change at 35% increase since 2011, and it crossed the single digit barrier beyond 10% and remain as such.

Two main challenges can be concluded to the structural deficiencies in Egypt. The first challenge is the rigidity and weakness of labor market facing external and internal crises, and the time to adjust to it. The second challenge is that unemployment reflects unhealthy labor market. New entrants to the labor market from the young people carry the main force and stress the current economic constraints. Young people account for nearly 22% of the Egyptian population, which they add about 600,000 new entrants each year that puts further pressure on the Egyptian labor market and with its already limited opportunities.

Labor market Structural deficiencies in Egypt

The socioeconomic characteristics of the unemployed in the Egyptian labor market reflect an inverted pyramid of unemployment, where unemployment rates rise among the educated, young, females, and urban areas. This is contrary to normal conditions in which the educated young population get better job opportunities in developed countries.

The main imbalances in the labor market is the occupation versus education mismatch in terms of both quantity and quality. From a quantitative perspective, the education system is fast growing in the labor market with a huge workforce annually that exceeds its ability to generate new job opportunities. Young people (age 20-24) represent only 12% of the total employed compared to more than twice this percentage (25.5%) for the population group age 30-39.

The main problem of the unemployment lies in the entering stage to the labor market. Most of the unemployed (60%) belong to the newly unemployed category, especially females (73% of the unemployed females have never worked before compared to 44 % of males).

As for the qualitative perspective, high unemployment rates among educated and its rise with rising education levels reflect the failure of education system to meet labor market required qualifications and skills. As seen in Figure 2 above, those with a university education and above represent the largest percentage of the unemployed, at nearly 50%. However, rates are significantly lower among the illiterate and those below secondary education level.

Also, the share of university graduates in employment are low, and approaches that of the illiterate and those who can read and write. The number of those holding a technical certificates are double that share, and 8 times higher than those who are above intermediate and less than university education. This is the result of the labor market’s strong bias towards certain sectors, such as building and construction, which they employ these groups.

Although data are not available by type of education, it has become a distinct phenomenon that only graduates of high quality university education are qualified to a decent sustainable jobs upon graduation.

The demographic structure

The proportion of the population in the working age has increased, which puts additional pressure on available job opportunities and economic activities. Also, Table 1 below shows the female participation in economic activity is very low compared to males, especially in the younger age groups, where male contributes in economic by 3-4 times higher, while these differences increase in other age groups.

|

|

|

Participation rate in economic activities |

||

|

Age group |

Labor force (%) |

Male |

Female |

Total |

|

15-19 |

5.2 |

21.7 |

3.5 |

13 |

|

20-24 |

12.8 |

52.3 |

16.1 |

34.9 |

|

25-29 |

17 |

91.1 |

22.9 |

57.1 |

|

30-39 |

25.2 |

96.5 |

22.8 |

60.3 |

|

40-49 |

19.7 |

95.9 |

22.6 |

60.3 |

|

50-59 |

15.8 |

89.1 |

21.5 |

57.6 |

|

60-64 |

2.8 |

44.7 |

5.9 |

26.7 |

|

65 |

1.5 |

20.3 |

2.5 |

11.8 |

Geographical distribution disparities of unemployment

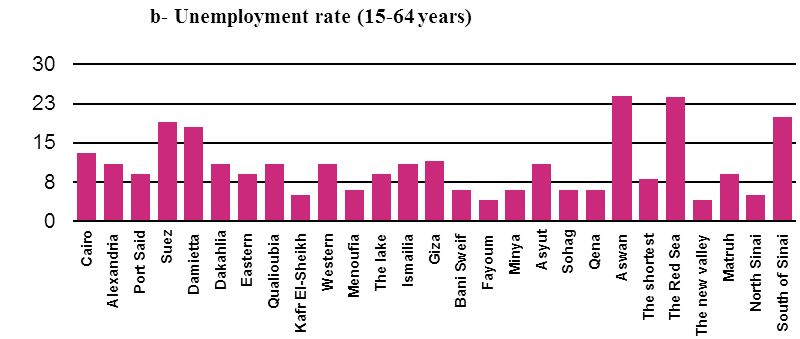

- Lower Egypt governorates are generally having the highest unemployment rates compared to Upper Egypt governorates, such as Aswan, which has an unemployment rate of 24%, Red Sea Governorate (23.5%) and North Sinai Governorate (48%); mainly due to the decline in tourism activity and the lower numbers of labor force in these governorates (Figure 3).

- In general, unemployment rates among young people in the age group between 15 and 29 are double the general average for the groups aged between 15 and 64.

- Finally, the geographical distribution of unemployment rates reflects great disparities between urban and rural areas nationwide, where urban areas having the largest share of unemployment compared to rural areas in general, due to the concentration of industrial activities in urban areas.

Figure 3. Unemployment rate by governorates, 2018

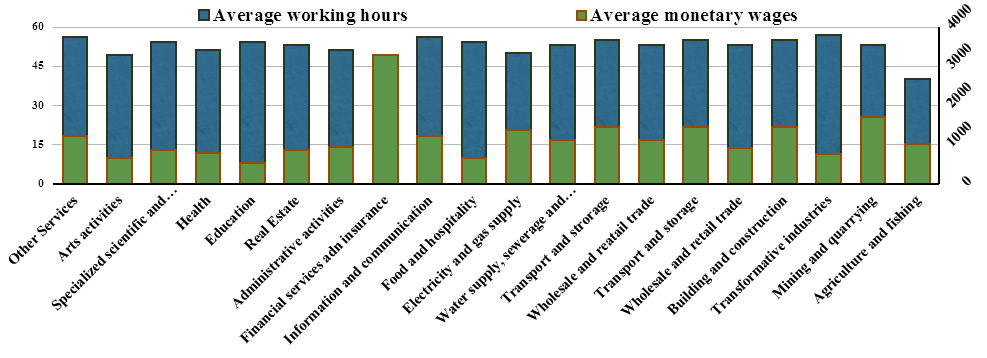

Between 2012 and 2018, wages have not adjusted to the higher inflation. The high inflation that followed the floating of the Egyptian pound has led to a significant erosion in real wages. The average real monthly wage decreased by 9% during the same period. Likewise, the average hourly wages decreased by 11%. Real wage declines were even higher among women, those working in urban areas, those with medium skills, and those working in the private sector compared to the public sector. Wage inequality has also sharply increased. One should note the difference between economic sectors in favor of specific sectors, provoke the average weekly working hours between 50-55 hours. Figure 4 below reflects that major service sectors such as health, education, and scientific research have the lowest return in the labor market; with the lowest average weekly wages compared to other service sectors such as telecommunications and information whose wages rates are 1.5, 2.3 and 1.4 times higher than the wages of the mentioned sectors.

Figure 4. Average working hours and wages on weekly basis, in economic sectors (2018)

Average wages vary greatly in favor of sectors of building and construction, financial intermediation, and insurance. The latter has the highest average weekly wage by more than 3 times than production sectors such as manufacturing and agriculture. Average wages/working hours also decrease in sectors that are most vulnerable to crises, such as tourism and wholesale and retail trade, falling below the general average by about 40% and 18%, respectively.

Economic growth patterns have long been characterized by its non-inclusiveness, especially in the aftermath of crises. As can be seen from Figure 5 below, the labor market response, represented in employment rates, lags behind the economic growth recovery point. This indicates a decline in the Egyptian economy’s ability to adjust to the developments in the labor market and absorb the unemployed after crises.

The share of public sector from employment reached about 25% of the workforce in 2006 compared to 26% in 2012. Employment rate and growth rate declined by 2.7% annually during the period between 2006 and 2012. The formal waged employment in the private sector witnessed a decline during the period from 2006 to 2012 by 3.4% compared to 7.1% in the period from 1998 to 2006.

Figure 5. Economic growth rates and employment rates over the three decades

Agriculture, manufacturing, building and construction, wholesale and retail trade accounted for the largest share of employment, followed by the transport and storage, food services and accommodation sectors during the fourth quarter of 2019. Higher-end jobs have witnessed a significant contraction in the labor market; in addition to the decrease in the share of professional and technical jobs, especially since 2015.

Figure 6. Employment rates by gender and age during the fourth quarter (2019)

The gender gap widens significantly in relation to employment rates, reaching 5-6 times more among males compared to females, especially among young age groups, similar with the past years, as shown in Figure 6 above.

Table 2 below indicates that the largest percentage of workers belongs to blue collar workers, as they account for more than half of the labor, followed by professionals and managers, and then white-collar workers. Looking at the details of the blue collar group, craftsmen represent the largest percentage 33%, followed by farmers and agricultural workers 29%, then workers in factories 22%. As for white-collar workers, 51% work in the service sector.

Table2. Percentage distribution of employed persons in the main professions, 2018

|

Main Professions |

Share of profession in total occupational category |

share of profession n total profession |

|

Legislators, senior officials and managers |

50.2% |

12% |

|

Specialists and scientific professionals |

49.8% |

11.9% |

|

Professionals and Managers |

100% |

23.9% |

|

Technicians and associate professional |

35.2% |

8.1% |

|

Clerks etc. |

13.7% |

3.1% |

|

Service and retail store workers |

51.1% |

11.7% |

|

Total White collar |

100% |

22.9% |

|

Farmers, agricultural workers and specialized fishing workers |

28.7% |

15.3% |

|

Craftsmen etc. |

33.4% |

17.7% |

|

Factory operation workers, machine operators and production assemblers |

21.6% |

11.5% |

|

Ordinary job workers |

16.3% |

8.7% |

|

Total Blue Collar |

100% |

53.2% |

Besides unemployment, underemployment is another major problem of the Egyptian economy. Poorly paid, low productivity jobs, both in the informal and formal sectors, bad working conditions and the lack of social protection affect a large portion of the Egyptian labor force. The Government uses to recruit double the number of employees actually need for its own structure which will arise major problems such in government expendi-ture relative to its productivity.

Self-employment

Only 9% of young population in Egypt are self-employed and this group comprises more male than female. The top reason is the expression of wanting greater independence. Another reason, they choose to earn a higher income at their own risk. Other self-employed young workers take it up because they cannot find a suitable paid job and about 10% were required by their family to follow the path of self-employment. The key challenges that self-employment are facing in running their businesses are the competition in the market, followed by insufficient financial resources and political uncertainty. Mainly, family, friends, personal savings served as the main source of financing for self- employed. The use of formal financial institutions is low (only 2.5% receiving financing from a financial institution).

Supply and demand shocks in the context of the corona crisis cycle

A few weeks after the Corona pandemic began, the estimated number of workers affected by the virus in early April at 2.7 billion people, or 81% of the world’s workforce. The severity ranged from reducing the number of working hours, lowering the wage, poor worker productivity due to the psychological effect of social distancing measures, and temporary or permanent layoffs.

In general, international surveys and estimates indicate that the continued closure of companies for one month exposes 20% of them to the risk of bankruptcy, this percentage increases to 40% if the lockdown continues for a period of three months without government intervention.

The most important facts of the impact of Covid-19 crisis on Egyptian labor market:

- Labor demand is derived from demand on final product or service, therefore is primarily affected. Production cut and marketing problems are directly transmitted to problems in labor demand for all sectors.

- Women are the most hit by the crisis among vulnerable categories, given their high representation in the service sector such as education, health, tourism.

- The impact of the crisis resulted to a job losses in companies and an increase in the unemployment rates in particular, especially in food services, leisure activities (cine-mas and theaters, hotels, etc.) and transportation (taxis, Uber, travel)

- The tourism sector have experienced a sharp decline in employment, whom its employees do not intend to search for other jobs, but rather awaiting the recovery.

- The government body does not lost its workforce, despite the freezing of 50% of the workforce. The export sector is generally one of the most hit sectors. It is clear that some businesses will stabilize faster than others. However, small enterprises that have gone bankrupt in all fields are not expected to return to operation, which will lead to an in-crease in the number of the new jobseekers.

- The low-skilled blue-collar workers are more likely to face job losses as a result of troubled manufacturing industries, while the problem for white-collar workers appears in the form of a salary cut of 30-50% or more. (shown in Table 2).

As a result of the crisis, an increase in severity of a problem in unemployment is expected, and its rates may reach 20% due to the return of workers from abroad. On the other hand, despite the importance of the role of medical sector and winning the government attention as a result of the crisis, a large number of doctors have decided to immigrate to the United States and European countries. These countries have opened the door to receive them, taking advantage of unsuitable working conditions in Egypt (low wages, and difficult working conditions), which will cause disruption in medical labor market in Egypt, and the economic industry as a whole. In the other hand, it will create vacancies and opportunities to replace.

Finally, Egypt’s entry into the crisis of COVID-19 and with a labor market suffering from many structural deficiencies has worsened the economic situation and increased its problems, as a result of education system that does not serve the market requirements, a disrupted wage structure, unemployment among young people, the absence of employ-ment opportunities in specific governorates as well as weak institutional and legislative framework. One of the positive points is that the crisis forced everyone to adopt and follow health safety measures and standards.

The interventions required to mitigate the effects of the crisis

According to the International Labor Organization, there are four main pillars to deal with the crisis and end up with the least losses in the labor market, as follows:

- Stimulating the economy and employment: this includes adopting active fiscal policies and monetary policies, while directing financial support and incentive pack-ages toward the most hit sectors, which directly reflects on the ability to boost the economy and to maintain workers.

- Supporting enterprises, jobs and incomes: extending the scope of social insurance to everyone, taking supportive retirement measures, and providing enterprises with financial relief and tax exemptions.

- Protection of workers in the workplace: enhancing occupational health and safety standards, adapting to emergency conditions such as working from home, preventing discrimination and exclusion between workers, providing health insurance and expanding access to paid leave.

- Adopting social dialogue to come up with sound solutions: enhancing the role of workers and trade unions and their collective bargaining power.

With regard to the unified minimum wage, the economic nature of each sector must be taken into account considering economic efficiency and given the existence of large differences among them in terms of labor intensity and productivity as well as profitability, being the most important element in determining the extent of the sector’s ability to pay appropriate wages to workers. Social justice also entails that minimum wage must be variable according to the standard of living, which varies from one governorate to another.

Institutional weaknesses revealed by the crisis

- The absence of accurate databases for supply and demand sides of the labor market that allow for effective coordination between them according to the skill level.

- The poor performance of the educational system, especially the technical and financial, and the need for a fundamental change therein to overcome the problem of structural unemployment permanently.

- The extreme weakness of the ability to invest in human resources in general, especially by the government, as it is the main factor responsible for many weaknesses in the Egyptian economy and labor market.

- Failure of employment policies to keep pace with labor market developments.

- Absent of the technological dimension and digital transformation from the employment system.